The tale of the duck and the whale

In 1971, Helmuth Bott, the head of Porsche’s vehicle development, convened his team in his office after the question arose as to why their customers could not compete with the BMW 2002s and the powerful Ford Capris on track. This issue was attributed to the sloping rear end of the Porsche 911, which acted as an airplane wing. As a result, the front end became lighter, providing little stability in fast corners. Efforts were made to find a solution aimed at minimizing the front lift of the Porsche 911. Allow me to tell you the tale of the duck and the whale.

Helmuth Bott’s team included Hermann Burst, Tilmann Brodbeck who had just graduated in aircraft technology and aerodynamics from the Technical University of Darmstadt and stylist Rolf Wiener. Brodbeck, who at the time owned a Fiat 850 Coupé 2+2 that he was fond of, as he mentioned in an interview with ‘Hagerty,’ exchanged it for a series II that came with a 5 hp performance increase and a little flick on the end of the engine cover. “I was astonished, it felt a lot faster, I knew it wasn’t possible with just 5bhp, so I asked the people at the Darmstadt wind tunnel if it could be the new engine cover – but they said it was just styling, nobody knew at the time,”. This experience prompted the development of the ‘ductail’ .

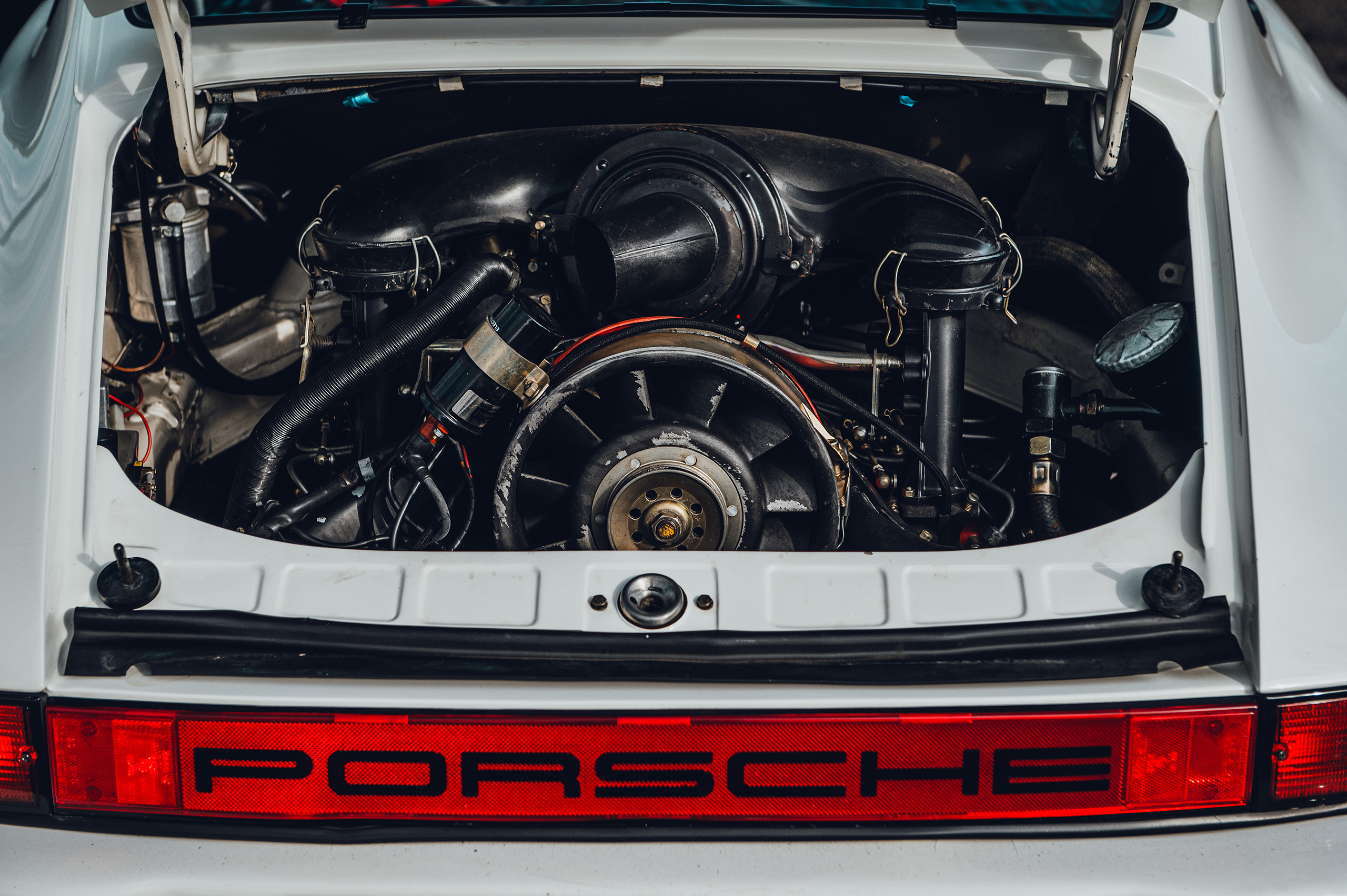

Who would have thought that finding a solution to a problem would give rise to an icon? Helmuth Bott, Hermann Burst, Tilmann Brodbeck, and Rolf Wiener had no idea. Various versions of a spoiler were crafted from sheet metal and wooden blocks to provide more stability to the Porsche 911. Initially, there was laughter about the design, which resembled the tail of a duck. However, Günter Steckhöning, an experienced racer, demonstrated the effectiveness of this spoiler: he achieved higher speeds and reported improved stability. With each iteration of the spoiler, the height was increased, resulting in an increase in speed and reduced air resistance for each iteration, until this gain in speed and resistance leveled off. Ultimately, an increase of 4.5 km/h was observed. To comply with safety standards for other road users, the tail was shortened to stay within the body lines of the car.

1972 Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7

Porsche was eager to emphasize the connection between street usage and race cars and introduced the Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7 (RS for Rennsport) at the Paris Motorshow in October 1972, which would feature these improved aerodynamic components designed for the then-current 911 models. “We wanted to improve traction and handling with wide tyres on the rear axle because the greatest weight is found on the rear axle” Peter Falk explains on the official website of Porsche. For this, the development engineers took inspiration from Porsche racing cars. Fuchs, who made the wheels, forged 6 J×15 wheels with 185/70 VR-15 tyres at the front, with 7 J×15 with 215/60 VR-15 tyres at the rear. To accommodate them, the car’s body at the rear, around the wheel arches, was widened by 42 mm. This was combined with a firmer-tuned, lighter suspension system and thicker anti-roll bars, lightweight aluminum front beams, reinforced control arms, and cross-member reinforcement at the back.

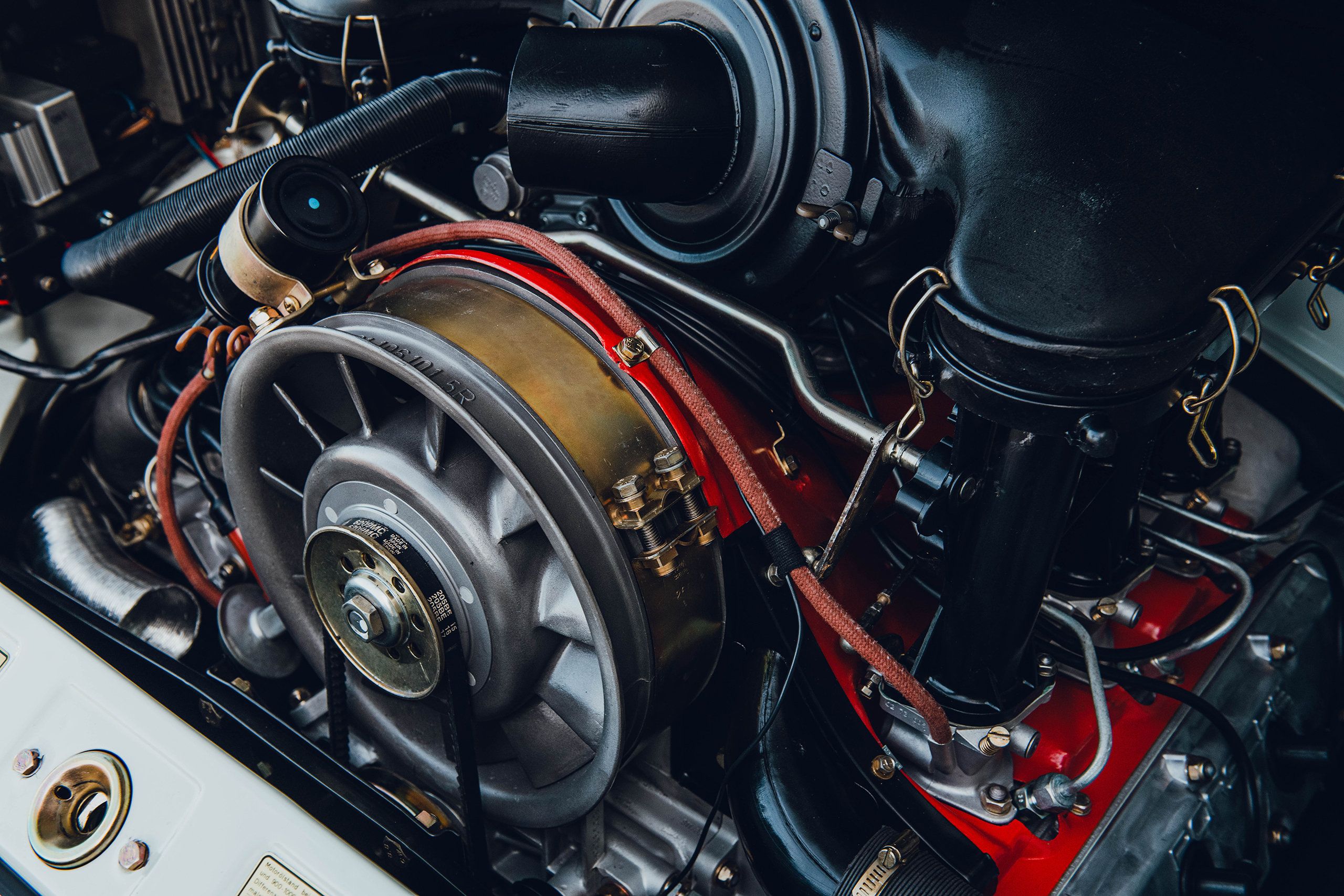

The Porsche 911 Carrera RS featured enlarged bores, increasing from 84mm to 90mm, resulting in a displacement of 2687cc. It maintained the same valves and compression as the 2.4, allowing the engine to unleash 207hp to the rear wheels at 6300 RPM. In addition to aerodynamic and engine modifications, Porsche also focused on weight reduction. Thinner sheet metal, reduced glass thickness, and the removal of sound insulation were implemented. The interior of the 911 Carrera RS 2.7 ‘Lightweight’ (M471) was stripped down to the bare essentials. Elements such as the rear seat, carpets, clock, coat hooks, and armrests were omitted. At the customer’s request, lightweight bucket seats replaced the heavier sport seats. Even the Porsche emblem on the hood was glued on. The eventual weight of the lightweight version was approximately 960kg. The marketing and sales staff doubted the concept of a fully stripped lightweight Porsche 911, pointing to the extremely limited production of the Porsche 911R in 1967, with only 20 units leaving the factory. Alongside the initial lightweight (M471) variant, which saw the production of 200 units, a more comfortable version was introduced – the Touring (M472). Certain components that were removed from the 911S for weight reduction were reintroduced in this Touring conversion, resulting in a final weight of 1093kg. The first batch of the Touring comprised 300 units.

The Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7 marked the very first Porsche to wear the name ‘Carrera’. The inspiration for the name was drawn from the Carrera Panamericana, a legendary (and highly perilous) Mexican road race that traversed from border to border in the early 1950s. In 1953, Porsche secured a memorable class victory with a Porsche 550 Spyder, followed by a third-place finish overall the year after. Subsequently, various powerful Porsche engines were already assigned with the ‘Carrera’ name. When a name was needed for the new top-tier 911, the newly designed lightweight Porsche stood out. ‘Carrera’ it read between the wheel arches on both sides in a color contrasting with the body paint, intersected by a broad stripe in the same color. This color scheme extended to the Carrera RS sticker on the ducktail and the Fuchs wheels, as well a thin line surrounding the car, for the lightweight conversion.

In order to qualify for participation in the Group 4 category for GTs and special touring cars, the Féderation Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) imposed a minimum production of 500 identical cars, each weighing less than 1000kg. However, the Touring variant exceeded this maximum weight, necessitating a solution from Porsche. Yet, at Porsche, they demonstrated cleverness, great cleverness: every Carrera RS underwent a complete strip-down and was taken to an official weigh station in Stuttgart, where the scale registered 935kg before being reassembled to the desired specifications. In the end, a total of 1580 Carrera RSs were produced: 200 Lightweights, the first batch of 300 Tourings with thinner sheet metal followed by 1008 later Tourings, 17 RSHs (H for Homologation), representing fully stripped units that were never reassembled to Lightweight- or Touring and received the ‘0’ conversion code. Additionally, there were 55 RSRs (RSR for Rennsport Rennen).

The Porsche 911 Carrera RS 2.7 established itself as the fastest German production car at the time.

1973 Porsche 911 Carrera RSR 2.8

In 1973, 55 RSH body shells were taken off the assembly line and transported to Werk 1, Porsche’s Racing Shop. The RSR was assigned the M491 code and underwent significant changes. They incorporated every conceivable improvement allowed by the FIA rulebook.

On the exterior, the most striking features of the RSR included the extremely wide fenders, accommodating the exceptionally wide tires and Fuchs wheels (9J x 15 at the front and 11J x 15 at the rear). The front spoiler featured an opening for the oil cooler, giving the RSR an aggressive look. Inside, the interior was further stripped down compared to the M471 conversion, which was already lightweight in itself. Porsche managed to save an additional 80 kg: a rubber mat covered the metal floor, leather straps served as door handles, minimal interior trim, and a half roll cage completed the interior. Notably, the interior boasted an extremely cool tachometer with a redline at 10,000 rpm.

The engine was enlarged to 2800cc by increasing the bore to 92mm, featuring larger valves, twin-plug ignition, and an increased compression ratio of 10.3:1. The six-cylinder engine (type 911/72) produced 300 hp at 8,000 rpm and maximum torque at 6,300 rpm. Suspension refinements and the 917-based braking system significantly enhanced handling and driving characteristics. Meanwhile, the RSR’s chassis was reinforced at three key points at the rear of the car to meet the demands of high-speed racing.

Surprisingly, the car clinched victory in its inaugural race, the 24 Hours of Daytona, straight out of the gate. Due to its non-homologation in Group 4, it had to compete in the prototype category, Group 5. The Brumos-entered car, driven by Gregg and Haywood, was the first to cross the checkered flag. Another Brumos entry two weeks later secured the overall win at the 12 Hours of Sebring, with once again Peter Gregg, Hurley Haywood, and Dr. Dave Helmick. Following Daytona, the Martini-sponsored factory cars claimed victories at Dijon and the grueling Targa Florio.

A new 3.0 engine and new aerodynamic features such as the ‘Mary Stuart’ tail and larger wheel arches that adorned the RSR allowed Porsche to set the fastest time at Le Mans testing, but finished fourth in the subsequent 24-hour race. These aerodynamic features were carried over to the Nürburgring, where Van Lennep and Müller finished in fifth place. Towards the end of the season, the factory experimented with the long-tail configuration, as seen in Zeltweg and Watkins Glen (now adorned in the Brumos and Sunoco liveries)..

1974 Porsche 911 Carrera RS 3.0

Porsche had considered discontinuing the 911 in 1974. However, they ultimately reconfigured their successful sports car to comply with the requirements of the crucial American market, which had introduced the 5 mph bumper impact regulation. Porsche also implemented some modifications to their lightweight Carrera RS model, resulting in the RS 3.0. By producing 100 units of this car, Porsche successfully homologated the RS 3.0 as an “evolution” of the RS 2.7/RSR 2.8.

Among these changes, the most significant include an enlarged, horizontal rear spoiler as an derivation of the ‘ductail’, wider wheels and tires, a cast aluminum crankcase, and slightly altered inner pivot points for the rear suspension. The broader wheels and tires necessitated wider fenders, which, for racing purposes, could be extended laterally by an additional 5 cm each to accommodate 11-inch-wide front and 14-inch-wide rear wheels. Upon delivery, the car features 8-inch forged aluminum rims at the front and similar 9-inch ones at the rear, shod with 215/60VR-15 and 235/60VR-15 Pirelli CN36 tires for both front and rear. Particularly intriguing is the fact that the cars were delivered with two types of the ‘whaletail’ spoilers. The smaller one, equipped with rubber protection, was intended for road use. This spoiler was deemed pedestrian-friendly and thus had to stay within the overall length of the car. For racing purposes, there was the larger spoiler with an additional opening for cooling.

Assuming that most of these RS 3.0’s would be purchased by people intending to race them, presumably with Group 4 modifications, as races for Group 3 cars are virtually nonexistent. Therefore, they decided to offer as many race-specific specifications as possible as standard: the car comes equipped with the cast crankcase, 95 mm Nikasil-plated aluminum cylinders, a large oil cooler for racing, a transmission oil cooler with the necessary pump built into the rear cover of the gearbox, and the immensely expensive drilled disc brakes developed for the 917 Can-Am turbocharged car!

Built upon a completely standars 911 body, the RS 3.0 featured integrated bumpers and front/rear lids out of plastic. The door panels are crafted from lightweight gauge-steel to maintain a low overall weight, and sound insulation is kept to a minimum for the same purpose. Thinner glass is selected for the side and rear windows to achieve additional weight savings. Additional weight reduction measures include a significantly simplified interior lining, the elimination of rear seats and other interior components and the substitution of standard seats with plastic bucket seats. The RS 3.0 is slightly heavier than the RS 2.7 and that’s not strange when you consider that the wheels and tires are heavier, and there are two oil coolers with their plumbing. Additionally, the aluminum crankcase weighs about 22 pounds more than the magnesium one of the standard 911 models. Overall the 911 Carrera RS 3.0 was heavier than the RS 2.7 but rest assured: it was just as fast! The five-speed gearbox was adopted from the 2.7 street cars, including a limited-slip differential as part of the package. The suspension was similar to that of the RSR models from late 1973, with a few detail changes, and the brakes were directly sourced from the 1973 RSR.

1974 Porsche 911 Carrera RSR 3.0

Porsche produced a total of 109 cars, with 55 built as Carrera RS for road usage and 54 as RSR models for racing purposes. As an evolution of the RSR from 1973, the 1974 RSR shared the same philosophy: it was a more aggressively prepared, further-stripped, race-ready version of its sibling, the Porsche 911 Carrera RS featuring a new 3.0-engine as tested at Le Mans in 1973. This resulted in one of the most successful Group 4 race cars of its time. While the RSR 3.0 was initially campaigned by the factory team, its real success came from being purchased and raced in large numbers by customer teams.

At the end of 1971, the mighty and quite possibly the most impressive race car ever, the Porsche 917, was banned from the circuit (except for the Turbocharged Flat-12 Can-Am cars that raced until 1974). Consequently, there were many spare parts and Porsche utilized the braking system and center-lock wheels from the Porsche 917. The even wider tires than those of the RS3.0 were accommodated in broader wheel arches equipped with an air intake that served as cooling for the brakes.

To save weight, fiberglass was used in the bumpers, hood, front lid, and the ‘Whaletail.’ Lightweight Perspex windows replaced the glass in the side windows for additional weight savings, and the interior was stripped down to the essentials. Porsche managed to bring the weight down to approximately 900 kg.

In addition to weight savings, particular attention was given to the flat-6 engine (911/75): it boasted a larger bore and a robust aluminum crankcase, replacing the magnesium one of the standard 911, to withstand the increased forces. The Type 911/75 flat-6 engine featured twin-plug ignition, high-lift camshafts, Bosch twin-spark fuel injection, a compression ratio of 10:3.1, dual megaphone exhausts, a dry sump oil tank, and retained the same 5-speed transmission as the RS. Generating 330 bhp at 8000 rpm and a torque of 232 ft lbs at 6,500 rpm, the substantial power increase was noteworthy. However, the more significant advantage for racing lay in the substantial improvement of reliability brought about by these modifications. The drivetrain was finalized with a reinforced clutch and a five-speed gearbox.

In 1974, the Porsche works team shifted its focus to the development and racing of a turbocharged variant of the 911, eventually giving rise to the 934 and 935 models. Consequently, the responsibility of campaigning the newly introduced Carrera RSR 3.0 now rested solely with privateers. Porsche continued the production of the RSR 3.0 through 1974 and into 1975, supplying these vehicles to customer racing teams.During this period, privateers experienced a unique advantage with a car that demonstrably outpaced their competitors. Frequently, multiple RSRs would contend for race victories, while other brands posed a challenge only as trailing contenders.

Johan-Franck Dirickx, whose love for lightweight Porsches began when his grandfather acquired a vibrant yellow 911 RS 2.7, currently possesses one of the largest 911 collections worldwide. This collection includes the RS/RSR models as featured in this story. In 2021 Johan invited me to spend some time with the RS 2.7, RSR 2.8 and RS 3.0 at Abbeville, missing out on the RSR 3.0. This year, I was invited once again by Johan to Abbeville, where we placed the RS 3.0 and RSR 3.0 side by side and turned the final page of the tale of the duck and whale.

Thanks, Johan, for sharing this experience!

From ‘Sport Leicht’ to ‘Sport Luxuriös’: This is the evolution of the Merc SL.

The Mercedes-Benz SL, born as a triumphant ‘Sport Leicht’ race car in 1952, transitioned into a road-ready model in 1955. Over the years, it has altered from its racing origins to become an integral part of Mercedes’ extensive model lineup. In earlier times, the SL represented a symbol of change and ambition; those driving SLs were considered visionaries aiming to reshape the world, for better or for worse. However, as time passed, the SL has lost its roots and the once-exclusive allure associated with the ‘playboy’ lifestyle. Today, Mercedes-Benz has seemingly taken a different route, possibly foreshadowed by the Mercedes-Benz 190SL W121 that debuted along the 300SL Gullwing at the New York show in 1954. The once rare and revolutionary SL is now a common sight on every street corner, prompting contemplation about the brand’s strategic turns over the years.

Mercedes-Benz 300 Sport Leicht W194 (1952-1955)

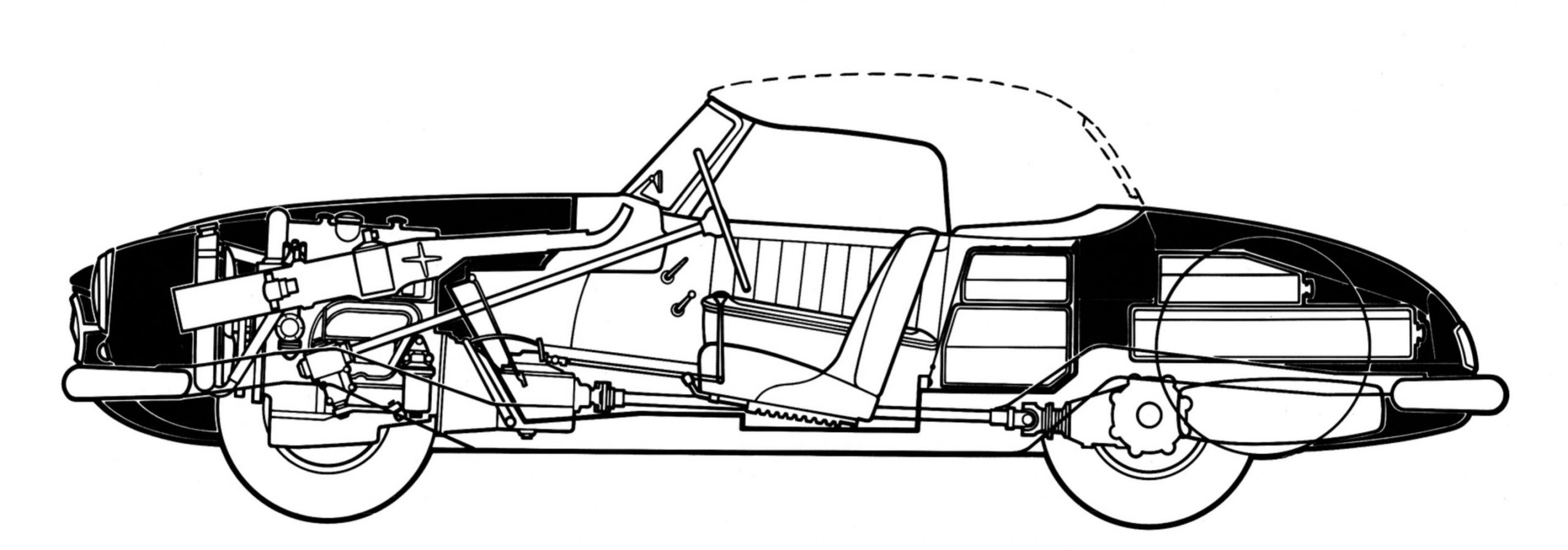

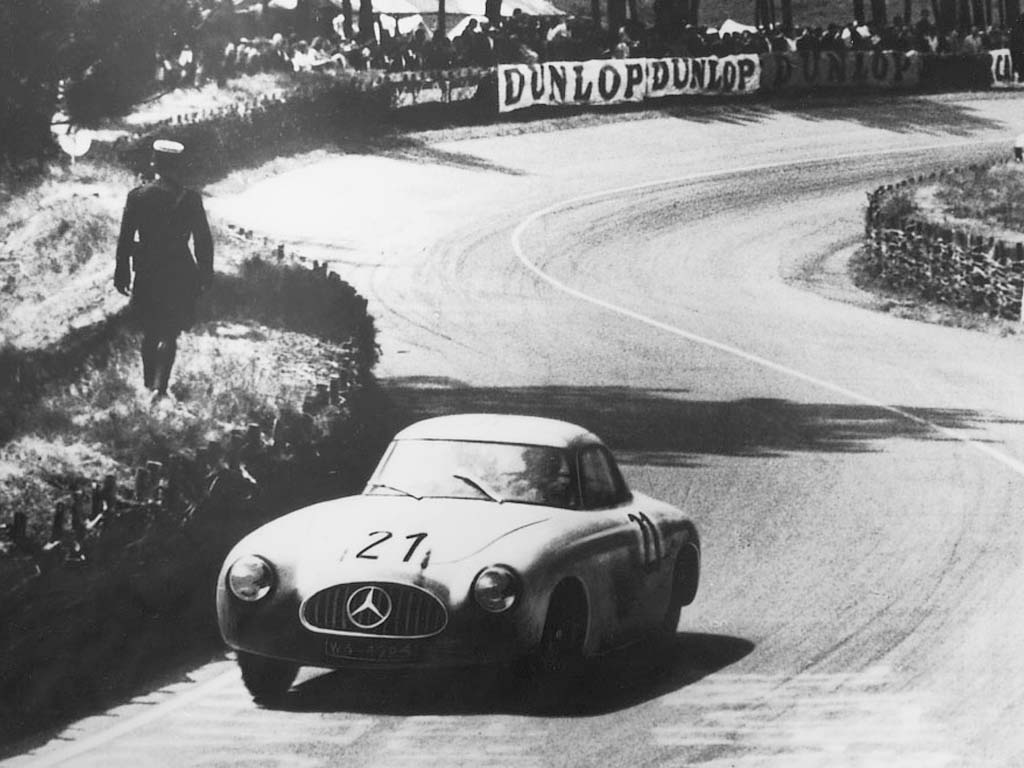

In the aftermath of World War II, the automotive industry in Germany faced a standstill as factories and engineers shifted focus to war-related efforts. But at Mercedes-Benz, they had a vision: to dominate 1950s sports car racing. The result was the birth of the Mercedes 300 ‘Sport Leicht’ or ‘SL’ in 1952 featuring a lightweight tubular frame crafted from aluminum and magnesium that weighed about 50 kilograms. The spaceframe design presented a structural conundrum: the elevated sill height left no room for conventional doors. The ingenious solution? Hinging them from the roof, causing them to ascend gracefully like the wings of a gull, thus giving birth to the iconic “Gullwing” doors. The initial versions of these doors extended just below the side window, making it a challenge for the driver to exit the car. The steering wheel could be tilted to make this process slightly easier, a feature that was also incorporated into the production model in 1955. Later versions of the gullwing doors reached approximately shoulder height for the driver when seated.

Rudy Uhlenhaut’s integration of a 3.0-liter six-cylinder engine from the contemporary sedan boosted power to an impressive 170 hp. The 1952 300 SL achieved remarkable success, securing victories in prestigious races like Mille Miglia, Le Mans, and Carrera Panamericana, leaving an indelible mark on the automotive industry.

Mercedes-Benz 300SL Coupé W198 (1955-1957)

Max Hoffman, importer of luxury European automobiles and visionary from the United States, appeared to grasp the market exceptionally well. He convinced Ferry Porsche to build the Porsche 356 Speedster, affordable and straightforward, the perfect foundation for a race car. Hoffmann was also the person who persuaded Mercedes at a board meeting to create a sports car for the American market, which would become a road-going version of the successful 300 Sport Leicht, the 300SL Coupé W198 (nicknamed Gullwing). Initially, much of the Mercedes team doubted the production story, as the 1952 300SL was rapidly assembled for racing. The Gullwing doors were not even considered beautiful at the time but rather a solution to a problem. During the same board meeting, Max Hoffmann ordered 500 cars, both 300SLs and 190SLs (Mercedes’ take on a ‘SL’ road car, but later on that). The production model of the 300SL Coupé was a well-thought-out finished product:

The 1952 Mercedes-Benz 300 Sport Leicht faced a significant drawback – excessive heat and noise within the driving compartment. This discomfort was attributed to the exhaust of air from the engine compartment through the drive line enclosure under the car’s floor. The initial solution, though not-so-effective, featured two narrow vertical vents ahead of the doors and smaller ones in the rear fenders – a somewhat unattractive design quickly replaced by the more familiar “egg crate” style seen in production cars. A pivotal resolution to this predicament involved fresh air intakes at the front grille and ductwork to introduce cool outside air into the passenger compartment. This intricate system also fed cool air through a double-wall firewall, efficiently dissipating engine heat. Concurrently, subtle yet transformative changes in body styling included reshaped fenders, wheel well openings, and the addition of mudguards or “eyebrows” over the wheel openings. The iconic oval grille with the three-pointed star at its center was introduced, becoming the unmistakable face of subsequent Mercedes-Benz sporting vehicles.

Under the hood, the engineers at Robert Bosch demonstrated their ingenuity by developing a piston-type injection pump capable of precisely metering gasoline to each cylinder. The injection quantity dynamically adjusted to the engine’s needs, as well as the air’s temperature and density, with injection pressure varying between 570 to 680 psi. Addressing further challenges faced by the 1952 race cars, changes included relocating the spark plugs into the cylinder head and installing fuel injection nozzles in the block openings. This innovative approach allowed the nozzles to spray from the cool to the hot side of the chamber, away from the spark plug. The 50-degree cant of the engine was retained to achieve Sindelfingen’s vision of a low hood line, allowing room for 17-inch ram induction pipes providing air to the engine. The 1952 300SL race cars had grappled with an awkward exhaust system arrangement, but with the introduction of those ram induction pipes, the exhaust lines could be strategically relocated under the intake manifold. The culmination of these innovations resulted in a breathtaking engine output of 215 hp (158 kW), propelling the 300 SL to a top speed of 250 km/h. This remarkable achievement secured the 300 SL’s status as the fastest production car of its era. Beyond its mechanical prowess, the 300SL represented a triumph in design and performance, a sentiment echoed by automotive enthusiasts and industry experts alike.

The Mercedes-Benz 300SL was a car for pioneers of the 1950s. The Shah of Iran owned one, as did Juan Peron, Juan Manuel Fangio, Clark Gable, Herbert von Karajan, among other trailbreakers. Even today, the 300 SL is considered the ultimate dream car. In December 1999, it was voted Sports Car of the Century by a jury of trade journalists.

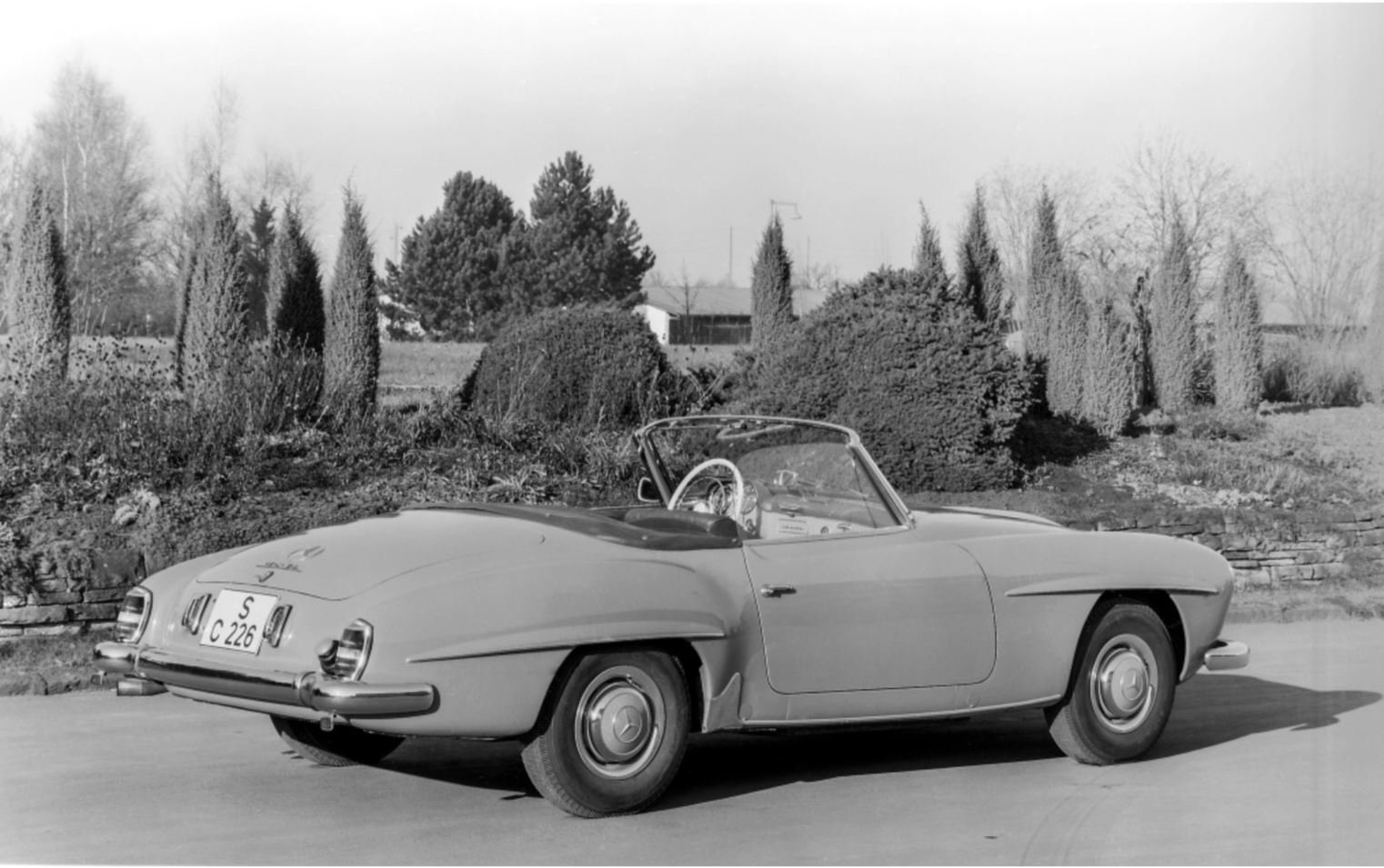

Mercedes-Benz 190SL W121 (1955-1963)

If we momentarily set aside the narrative of the 300SL and begin with the 190SL, the evolution of the SL series appears to align more or less. However, we can’t simply disregard its origins. Originally, Mercedes-Benz envisioned building a roadster on the hefty Mercedes 180 W120 ‘Ponton.’ Yet, Max Hoffman insisted that the SL should resemble the 1952 racing car. Consequently, Mercedes introduced both the 300SL and the 190SL in 1954.

In today’s context, a Mercedes 180 W120 ‘Ponton’ can be likened to an S-class, somewhat cumbersome. With its chassis and as many recycled components as possible from the 180, along with its robust 105hp 1.9-liter 4-cylinder engine, the 190SL was undeniably hefty. Hefty but beautiful. Beautiful but expensive. Expensive but not 300SL-expensive, yet not as swift. And so, the circle is complete. The 190SL demonstrated that Mercedes-Benz recognized people often chose elegance over performance. Was it about elegance? Or was it status? Remember how those who aimed to change the world often drove SLs. You could drive one yourself now, too.

Mercedes-Benz 300 SL Roadster W198 II (1957-1963)

In 1957, Mercedes-Benz likely instructed Uhlenhaut to develop the 300SL roadster, marking the end of the Gullwing era. The decision might have stemmed from reservations about the Gullwing doors (Mercedes really didn’t like them, did they?), leading to the introduction of a more universally appealing roadster.

The midsection truss frames of the Roadster were lowered by 50%, enabling the use of standard doors. The standardization of the competition camshaft and the optional high compression ratio engine (9.5:1), providing an increased engine output of 250 bhp, were notable upgrades. Belly pans were eliminated, and the steering transitioned from 2 to 3 turns lock to lock. However, these enhancements resulted in an added weight of over 90kg, with the curb weight going from approximately 1300 to 1400kg. Consequently, the standard rear axle ratio was adjusted from 3.64 to 3.89:1.

Weight was not the only thing that had increased, so did the new price. The 300SL coupes were sold for $8,905, whereas the starting price for the roadster was $10,970. A total of 1858 roadsters were manufactured before the discontinuation of the 300SL model in 1964.

In numerous aspects, there is no doubt that the roadster surpasses the 300SL Gullwing as a superior car. The suspension roll center was brought down by incorporating a low pivot rear axle with a helper spring, effectively reducing roll stiffness. This modification enhances the car’s adaptability to different tire types, and notably, the Michelin X steel-belted radials were included as standard factory equipment. In their road test of the vehicle, Road and Track magazine noted, “…..the car handles beautifully under all conditions.”

Mercedes-Benz SL W113 'Pagoda' (1963-1971)

The focus of the Pagoda shifted away from creating a super-light sports car and even further from motorsport (although an almost standard 230SL won the Spa-Sofia-Liege rally). Instead, it aimed at creating an open-top GT car, something between the 300SL and the 190SL—sporty yet luxurious. Features like a mirror on the passenger side and a radio were standard. Automatic transmission and power steering were commonly chosen options. Many consider the Mercedes Pagoda as the best SL. Celebrities such as John Lennon, Tina Turner, and Priscilla Presley owned one. Contemporary owners include David Coulthard, Emma Bunton, and Harry Styles.

The Pagoda’s design team, led by Friedrich Geiger, likely saw contributions from designer Paul Bracq and engineer Béla Barényi. The unique concave bow of the hard-top roof, designed by Barényi, earned the car its nickname “Pagoda,” because it looked like a Japanese Pagoda roof.

Barényi played a significant role in passive safety too, introducing the crumple zone. The W113 was hailed as the ‘first sports car worldwide with a safety body consisting of a rigid passenger cell and front and rear crumple zones.’ Safety features, including three-point safety belts, were added in 1966, well ahead of legal requirements.

The W113 shared the basic inline-6-engine block with the W111 saloon but underwent revisions for a more sporting application. The six-plunger injection pump, a notable change, significantly increased power by allowing more direct fuel injection into pre-heated intake ports. The mechanical injection system in the W113 was advanced for its time, adjusting for atmospheric conditions and using coolant temperature monitoring for efficient fuel metering.

Despite using aluminum in many sections, the Pagoda still weighed nearly 1400kg, considerably more than contemporary Jaguar E-types or Porsche 911s. Yet, at the press launch on the Montroux circuit, Rudolf Uhlenhaut, at age of 57, drove the 230SL impressively fast, just 0.2 seconds slower than Mike Parkes in a more powerful Ferrari 250 Berlinetta, proving the true sports-car-status of the Merc Pagoda.

Within the evolution of the W113, a shift towards luxury over performance is evident. Many 230SL owners chose manual, while most 280SL owners preferred automatic. This trend continued in the R107 generation. During its eight-year production run, the W113 sold 48,912 units, with the majority being 280 SLs. The Pagoda was not cheap. A 280SL with hardtop, automatic transmission, and power steering was nearly double the price of a Jaguar E-Type 4.2.

Mercedes-Benz SL R107 (1971-1989)

In the wake of the iconic ‘Pagoda,’ the Mercedes-Benz SL R107 took the stage, poised to meet the high standards set by its predecessor and satisfy the discerning clientele of Mercedes. This generation of SL was distinctly crafted for luxurious grand touring, shedding the aura of a sports car for the allure of a refined GT vehicle. It was designed not just to traverse the country smoothly and comfortably but to do so in style, marking a departure from the sports car ethos.

Prioritizing safety and comfort, the R107 SL earned the moniker ‘Panzerwagen.’ Robust crash structures and a padded four-spoke steering wheel underscored the commitment to safety. However, with safety and comfort comes added weight, a departure from Mercedes’ initial ‘Sport Leicht’ philosophy. Despite this, the R107 SL was endowed with performance through a V8 engine derived from its larger saloon counterpart.

The SL made its debut with a 350 and 350 4.5, the latter being rebranded as the 450 in 1973. In response to the fuel crisis of the early 1970s, Mercedes introduced the 280SL in 1974, equipped with a robust six-cylinder engine. From then on, the series consistently featured a six-cylinder engine; the 300SL replaced the 280 in 1985 and remained in production until the discontinuation of the model. Various versions with V8 engine capacities were offered, including the 380, 420, 500, and the 560SL as the ultimate Mercedes roadster.

Throughout its lifespan, the R107 SL evolved with technological advancements. From March 1980 onwards, it featured ABS anti-lock brakes, and by the beginning of 1982, a driver’s airbag became an optional feature. In early 1980, the previously optional hardtop became standard equipment across all SL models, adding to its overall allure. Even as the model approached the end of its production, Mercedes continued to innovate, introducing a closed-loop catalytic converter for all versions from mid-1985.

The R107 SL would go on to become the longest and most produced SL generation, with an impressive 18 years in production and a total of 237,287 units built between 1971 and 1989. Despite its superiority over the Pagoda, the abundant availability has kept prices relatively affordable, unlike the ‘Pagoda’ models that have become a distant dream for many enthusiasts.

The allure of the Mercedes-Benz SL R107 extended, just as previous generations, beyond enthusiasts to the celebrities. From Donna Summer and Ben Stein to Madonna and Bruce Lee, a plethora of notable figures chose to cruise in the timeless elegance of the R107, solidifying its status as a beloved classic among the stars.

The 450SLC (C for Coupé) 5.0 not only participated, but also emerged victorious in the 1978 Vuelta à la América del Sud rally, spanning 10 countries in South America from Argentina to Chile. Four 450SLCs were entered and remarkably, three of them clinched top positions, securing first, second, and fourth places, while a Mercedes-Benz 280E claimed third. The magnitude of these pan-continental rallies cannot be overstated. The Vuelta à la América del Sud covered nearly 18,000 miles of challenging terrain, including mud, gravel, and rutted tracks. Despite being built on the chassis of a swift German executive coupe, the SLC demonstrated remarkable toughness, enduring the harsh elements. Oh, and it rallied with its automatic 3-speed gearbox, making it the first car to win a World Rally Championship event with an automatic gearbox.

After the 300SL W192 succes, the three-pointed star became a rare sight on the circuit. A lesser known hero was the Mampe-sponsored one-off AMG Mercedes-Benz 450 SLC that out of nowhere appeared in 1978 on Silverstone.

Mercedes-Benz SL R129 (1989-2001)

By the advent of the R129 generation of the SL, it seems Mercedes might have been playfully toying with the very essence of the ‘Sport Leicht’ name, especially when equipped with a V12 engine that nearly tips the scales at 2 tons. Despite this weighty paradox, the R129 stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Mercedes’ iconic SL series, capturing the hearts of enthusiasts for compelling reasons. The R129 marked the conclusion of an era where celebrities were drawn to the ownership of the SL. Princess Diana exchanged her Jaguar for an SL and got in trouble for it.

As each generation adds more heft, as does this gen SL, the R129 must live up to its legacy by amping up the power. The R129 SL500 boasts a 24-valve 5.0-liter V8 with dual camshafts, delivering a robust 322 horsepower, while the R129 SL600 commands attention with its formidable 6.0 V12. Even the entry-level six-cylinder variant outpaces its V8 predecessor, the SL R107.

Beyond its sports car ambitions, the R129 showcases technological prowess with an unwavering focus on comfort. Pioneering features such as brake assistance, stability control, and active damping, seamlessly integrated with a self-leveling suspension, redefine the new SL concept. From rain-sensing wipers to passenger seat occupant detection, ensuring airbag deactivation for seats weighing less than 10 kg, and a central locking system that operates on both storage compartments and doors, the R129 embodies undeniable luxury and sophistication.

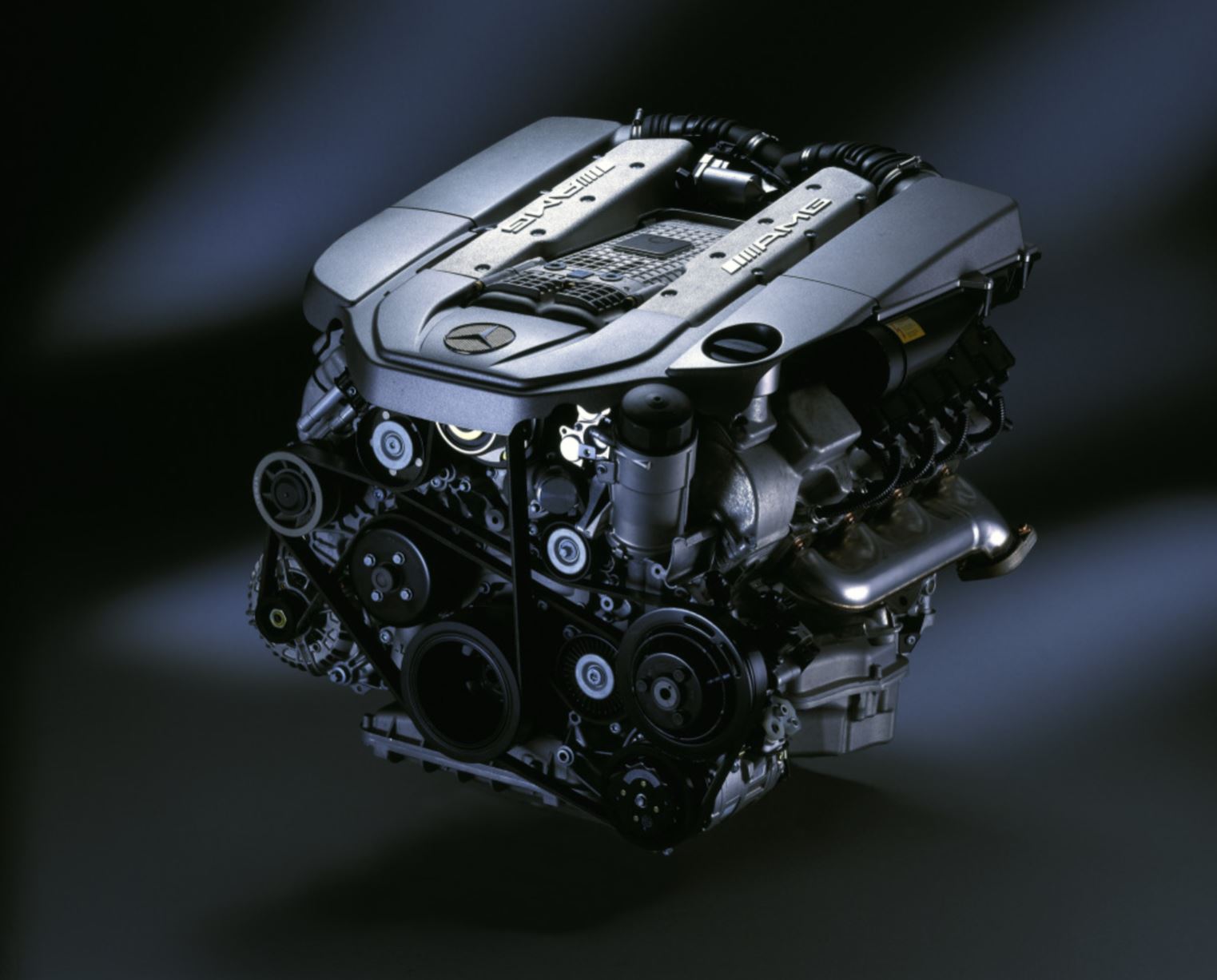

A significant turning point in the R129’s narrative comes with its distinction as the first SLs available with AMG tuning, predating Mercedes’ majority stake acquisition in AMG. This era witnesses the birth of the official AMG model in 1993, the SL60 AMG. In 1999 the formidable SL73 AMG was introduced, housing a 525bhp 7.3-liter V12—an engine that would later find its way into the Pagani Zonda.

Navigating the contradictions embodied by the R129 SL, it emerges not only as a heavyweight champion in power but also as a technological trailblazer, challenging and redefining conventional notions of the SL. The R129 not only pays homage to its lineage but also sets the stage for the next thrilling chapter in the evolution of the Mercedes-Benz SL series.

Mercedes-Benz SL R230 (2001-2011)

Stepping back more than two decades, the earliest versions of the SL R230 hold a special place in my heart as the generation I grew up with, encapsulating a sense of nostalgia that makes it incredibly appealing to me. However, beyond the emotional connection, to truly understand the evolution of the SL series, one must delve into the facts.

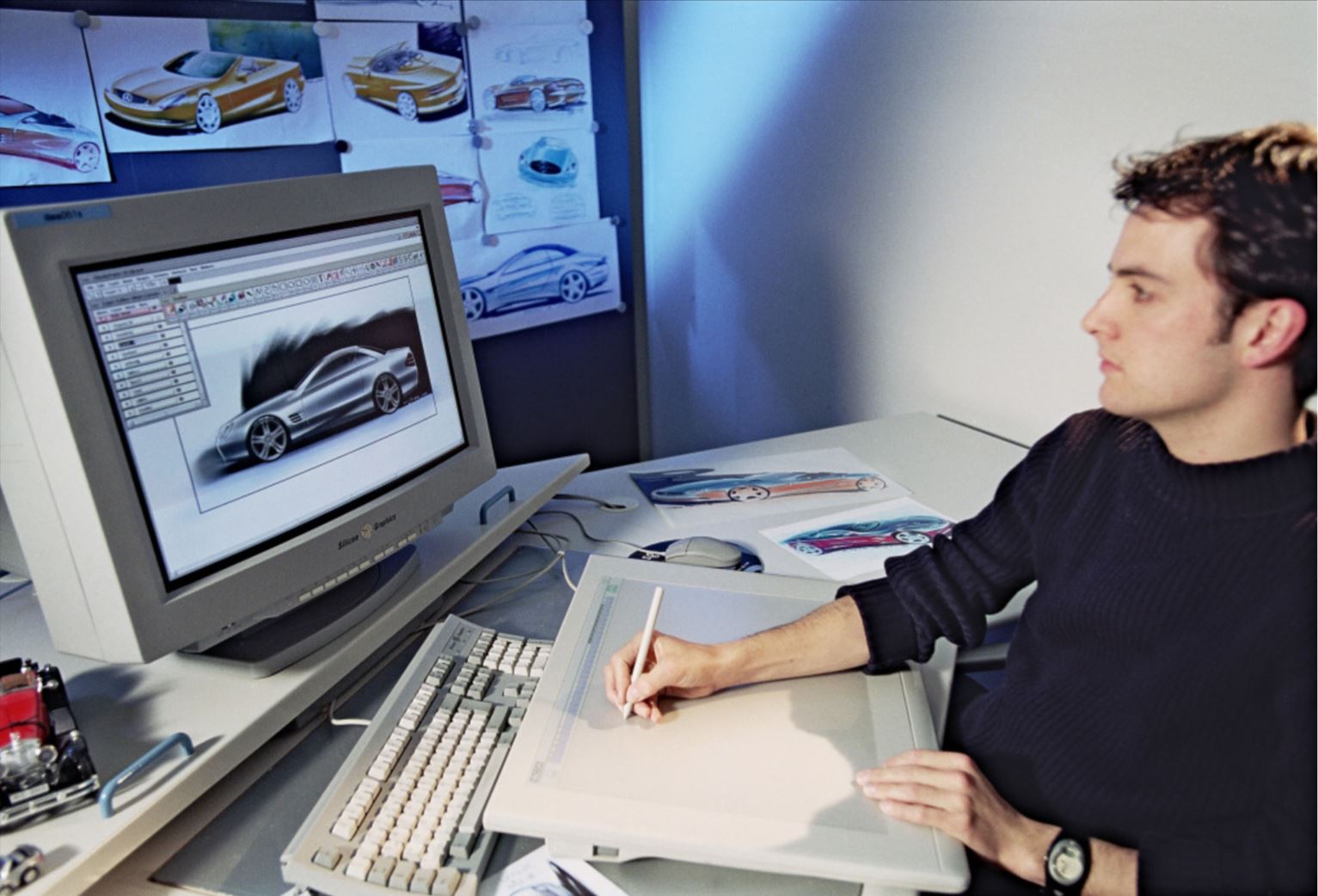

The press was ablaze with enthusiasm upon the launch of the R230, praising its groundbreaking design language. Similar to its predecessors, this generation utilized cutting-edge technology, notably the use of a 3D super-computer named ‘CAVE.’ This revolutionary computer projected full-sized images through five projectors, allowing for a meticulous digital inspection of all surfaces – a first in the automotive industry. The R230’s design, ahead of its time (yet with a nod to the past), featured four headlights and a unique two-in-one convertible/hardtop roof comprised of foldable metal plates, with an optional panoramic roof. The SL500 version was also built with ABC – Active Body Control, part of the car’s new adjustable air suspension system, offering various suspension stiffness settings with automatic control and adjustable ride height. The SL350 featured traditional coil springs (although ABC was optional), adaptive cruise control, automatic xenon headlights, COMAND-based in-car entertainment with sat-nav, standard dual-zone digital climate control with AC, keyless go, an on-board computer and electric heated memory seats with optional seat cooling and massage function. It seems the SL series served as a canvas for Mercedes to apply technological innovations rather than simply developing a super light sports car. The side air intakes pay homage to those of the iconic 300SL W198, though.

A true modern SL wouldn’t be complete without an array of engine options. At launch, the R230 offered the SL500, equipped with a 5.0-liter V8 M113 (302 hp), and the SL350 featuring the M112 (242 hp) 3.7-liter V6. In 2003, the formidable SL55 AMG entered the scene, boasting the M113 5.5-liter V8 with a supercharger, producing a staggering 493 hp and 700 Nm of torque – a symphony of performance and sound. The more refined SL600, introduced in the same year, shared the SL55’s power but with additional torque, courtesy of its 5.5-liter V12 twin-turbo engine. The 2004 SL65 AMG took it a step further with the M275 6.0-liter V12, delivering a whopping 604 hp and 1000 Nm of torque, exclusively driving the rear wheels through an automatic transmission.

Yet, the ultimate question persists: Does the SL R230 deviate from the initial ‘Sport Leicht’ concept? Weighing in at just under 1700kg for the 6-cylinder version and nearly 2000kg for the 12-cylinder variant, it becomes clear that this generation prioritizes comfort, safety and performance over weight reduction, leading us to characterize it as ‘Sport Luxuriös.’

Mercedes SL R231 (2012-2020)

In the illustrious lineage of the Mercedes-Benz SL series, the R231 stands as the sixth iteration, blurring the lines between ‘Sport Leicht’ and ‘Sport Luxuriös’ even more. Shedding its lightweight aspirations, a trait it never truly embraced, especially when tracing its roots back to the 190SL rather than the iconic 300SL, the R231 is more than just a generational shift – it’s yet another transformation of the SL’s identity.

Is it still appropriate to categorize this generation as a sports car? Or even a tourer? The dichotomy between sportiness and touring comfort seems to have shifted with the R231, leaving enthusiasts pondering Mercedes-Benz’s direction for this generation. Also the status associated with owning an SL faded away with this generation.

Aesthetically, the R231 draws inspiration from the iconic 300SL W198 even more than the SL R230, featuring a broad grille, a three-pointed star enclosed in a grand circle, a singular vertical line cutting through the grille, side vents, and distinctive headlights. This classic appeal seamlessly extends to the interior, where quality reigns supreme with a combination of leather, wood, and metal, especially in the range-topping models. Interestingly, Mercedes chose to showcase all previous generations fort he press release, except for the R230, emphasizing the R231’s departure from its grandfathers. Well, at least in terms of design.

Built on a lightweight aluminum chassis, the R231 offers a dynamic driving experience powered by a 6- or 8-cylinder engine, depending on the version. Notably absent from the standard lineup is the 12-cylinder powerhouse, now reserved for AMG enthusiasts willing to delve into six-figure price tags. The chassis features multi-link suspensions at all corners, with aluminum components at the front control arms and steering knuckle to reduce unsprung weight. The suspension setup includes steel springs and electronic adaptive damping as standard, while Active Body Control (ABC) suspension remains an enticing optional feature. The steering system undergoes a modern shift with electromechanical assistance, enabling variable gear ratios and speed-sensitive assistance.

At the zenith of the R231 lineup, the SL500 follows the philosophy of the 190SL W121, prioritizing style, design, and technology over sheer driving pleasure. For those seeking an adrenaline rush, the SL63 AMG with its 5.5-liter twin-turbo V8 and the SL65 AMG featuring a 6.0-liter twin-turbo V12 offer an exhilarating alternative, albeit with a price tag that commands attention.

Mercedes-Benz SL R232 (2022-now)

The seventh iteration of the iconic SL series, the R232, appears to herald the revival of the ‘Sport Leicht’ philosophy. While not exactly featherlight (1875kg for the SL55 and 1895kg for the SL63), it boldly reclaims its sporty heritage under the exclusive supervision of Mercedes-AMG. This strategic shift is driven by the brand’s recognition of a declining trend in sales for luxury roadsters, attributed to the rising popularity of crossovers and SUVs.

The SL500, once synonymous with luxurious roadster prowess, takes a backseat as Mercedes refocuses on injecting a renewed sense of sportiness to boost sales. To avoid encroaching on the AMG-GT territory, Mercedes ingeniously introduces two extra seats, harking back to the 2+2 configuration last seen in the R129. Is Mercedes acknowledging that the earlier SL generations were the most captivating?

In a bid to compete with the Porsche 911 Cabriolet and trim down weight, Mercedes makes a daring move by reverting to a fabric soft-top. The R232 not only nods to the 1952 300SL W194 visually with the ‘Panamericana’ grill but also features an aluminium space frame, making it more original-SL-like than any other generation.

The 6 and 12-cylinder engines bid adieu in the R232 lineup. Both the SL55 and SL63 now boast a twin-turbocharged 4.0-liter V8, each distinguished by turbo configurations and intake systems. The SL55 delivers around 483 hp and 700 Nm of torque, hitting a top speed of approximately 294 km/h and accelerating from 0 to 100 km/h in about 3.8 seconds. On the other end, the SL63 elevates the performance to about 594 hp and 800 Nm of torque, achieving a higher top speed of around 316 km/h and a faster 0 to 100 km/h acceleration in about 3.5 seconds. The swift launches are facilitated by the standard use of the 4MATIC+ system and a 9-speed MCT gearbox – marking the first all-wheel-drive SL.

Also this generation also serves as canvas for their technological innovations: the R232 introduces groundbreaking chassis dynamics. While the rear axle retains the multi-link setup, the front suspension shifts from a 4-link to a 5-link configuration, neatly housed within the wheel rim. As an exclusive AMG model, the SL opts for conventional steel springs over the air suspension preferred in other Mercedes production cars. The SL55 comes equipped with adaptive dampers, while the SL63 introduces a revolutionary suspension technology named “Active Ride Control.” The four-wheel-steer system counters the longer wheelbase and additional mass, enhancing maneuverability and reducing turning radius.

Mercedes brings Formula 1 technology to the streets with the SL43 AMG: it pioneers an electrified exhaust gas turbocharger, a first for road cars. Based on the existing M139 2.0-liter four-cylinder engine found in the A45, the SL43 prioritizes refinement and driving dynamics. Replacing the traditional turbo with a smaller electrified counterpart eliminates turbo lag, resulting in 381 hp at 6750 rpm and 354 lbft of torque from 3250 to 5000 rpm. This forward-thinking approach positions the SL43 AMG at the forefront of automotive innovation.

In conclusion, the question arises whether Mercedes has strayed too far from the original SL ideology over the years. While the SL has served as a canvas for the integration of new technologies, the introduction of the R232 suggests a return to making a bona fide sports car that draws inspirations from the motorsports. The future remains uncertain, inviting anticipation for what lies ahead in the evolution of the SL series. My question remains: when was the last time you craved having an SL?

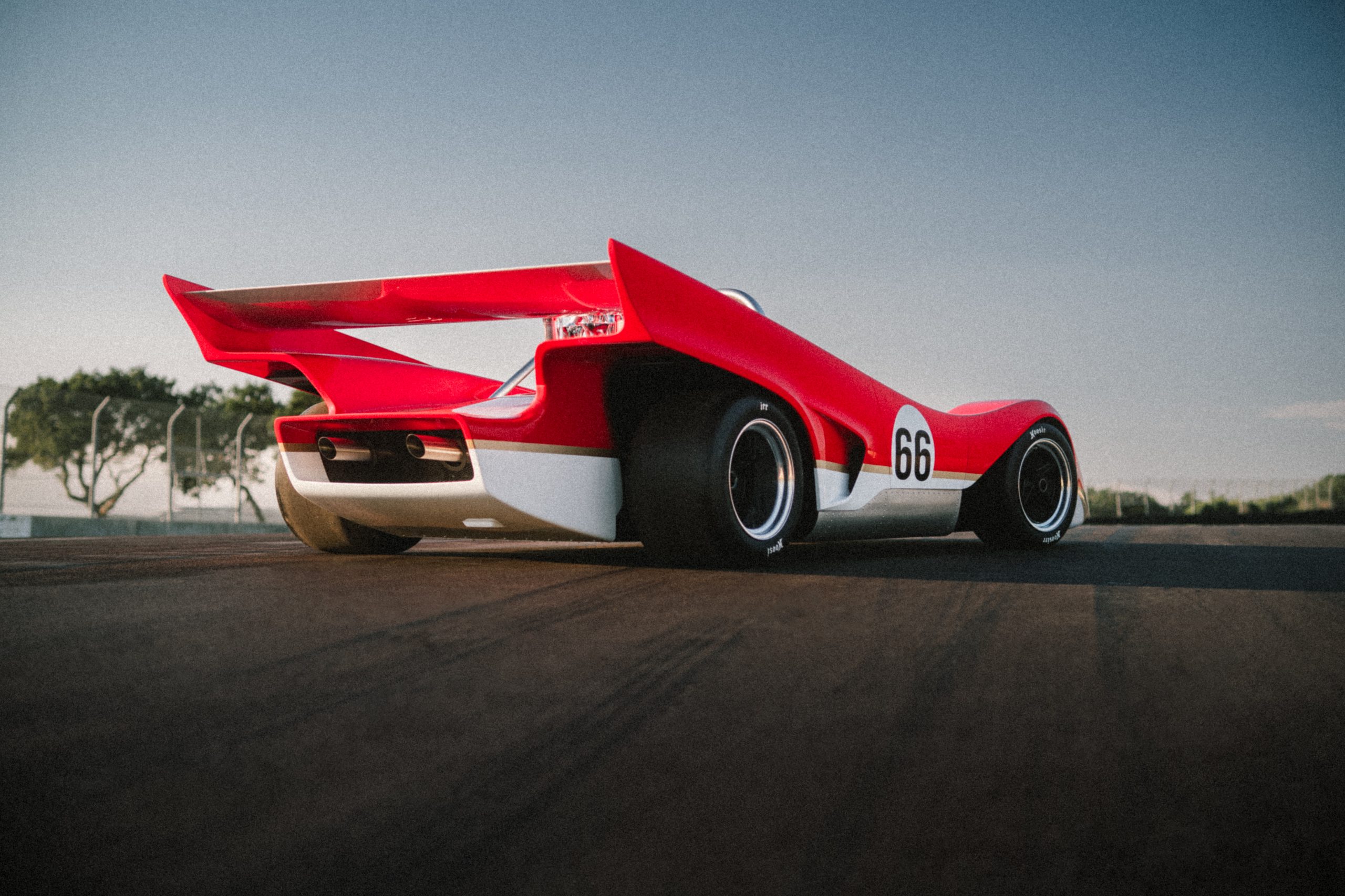

Blow the trumpets: The Lotus Type 66 ‘Can-Am Racecar’ is finally here after 53 years.

Lotus turned 75 this year, a remarkable achievement itself. A reason for celebration. In honor of this anniversary, Lotus unveiled the Type 66 Can-Am Racecar: a long-forgotten concept from the ’70s that was intended to grant Lotus entry into the Canadian-American Challenge Cup (or Can-Am). After 53 years the Lotus Type 66 finally departs from the drawing board and heads towards production line, where only 10 copies will be produced. Happy Birthday, Lotus!

Fifty-three years ago, Lotus aimed to diversify its presence by entering the Canadian-American Challenge Cup alongside its Formula 1 pursuits. Colin Chapman entrusted designer Geoff Ferris with the task of encapsulating everything that Lotus stood for in a Can-Am race car to enter the Canadian-American Challenge Cup. However, due to the unseen success in Formula 1, the Can-Am project never advanced beyond a few sketches and scale models and was shelved. Now, 53 years later, Lotus has rewritten its history: Past and contemporary technologies converge seamlessly embodied in the Can-Am racer wearing its iconic red-white-gold livery. A limited production of only 10 units is planned, symbolizing the intended number of races the Type 66 would have entered, creating a true testament to Lotus’ racing heritage.

“The Type 66 perfectly blends the past and present. It takes drivers back in time, to the iconic design, sound and pure theatre of motorsport more than 50 years ago, with added 21st century performance and safety. This is a truly unique project, and in our 75th anniversary year, it’s the perfect gift from Lotus fans worldwide and to a handful of customers,” said Simon Lane, executive director of Lotus Advanced Performance. “While the visual expression is strikingly similar to what could have been—including the period-correct white, red and gold graphics—the technology and mechanical underpinnings of the Lotus Type 66 represent the very best in today’s advanced racing performance.”

Leveraging cutting-edge computer software, the team under the leadership of Russell Carr, Lotus’ design director, digitally transformed a series of 1/4- and 1/10th-scale drawings provided by Clive Chapman, son of. They built 3D renderings, offering a fresh perspective on the vehicle. The initial sketches faithfully adhered to Colin Chapman’s early designs, showcasing a cockpit enclosure designed to reduce drag and enhance airflow to the rear wing. Clive commented, “The car would have shared many innovative features with our most successful F1 chassis, the Lotus Type 72, which was developed during the same era. It would have been spectacular, as is the actual Type 66 we see today.”

The updated aspects of the vehicle include a modernized driver compartment, an inboard fuel cell, a sequential transmission, and an anti-stall system. All accommodated within a fully carbon-fiber body shell. The design of the front wing aims to guide air from the car’s front, directing it through and underneath the rear wings. This configuration generates more downforce than the vehicle’s total weight when racing at full speed. This concept of porosity, allowing air to pass through the vehicle rather than around it, has become a distinctive hallmark of Lotus vehicle design as seen on the Emira sports car and Evija hypercar.

“We are incredibly proud to have completed such a unique project, and one that Colin Chapman was personally involved in,” said Carr. “There is a real delicacy in remastering the past. This is not a re-edition or a restomod, but a completely new breed of Lotus—a commitment that our past glories will continue to be reflected in our future.”

At the heart of the Type 66 lies a V8 push-rod engine representative of its era. Positioned mid-mounted for optimal handling, Lotus has fine-tuned it to yield over 830bhp at 8,800rpm. Incorporating contemporary, custom components such as a forged crank, rod, and pistons, the engine generates a torque exceeding 746 Nm at 7,400rpm. The distinctive Can-Am-inspired air intake ‘trumpets’ prominently adorn the showpiece of the engine. These not only streamline the air intake to foster laminar flow, ensuring a smooth power delivery and enhanced driveability.

Could Lotus have achieved even greater dominance in 1970s racing if the Type 66 had graced the starting lines of the Can-Am races?

The Lotus Type 66 was unveiled at ‘The Quail, A Motorsport Gathering’ as part of Monterey Car Week 2023 in California, USA. Photography by David Coyne for Lotus.

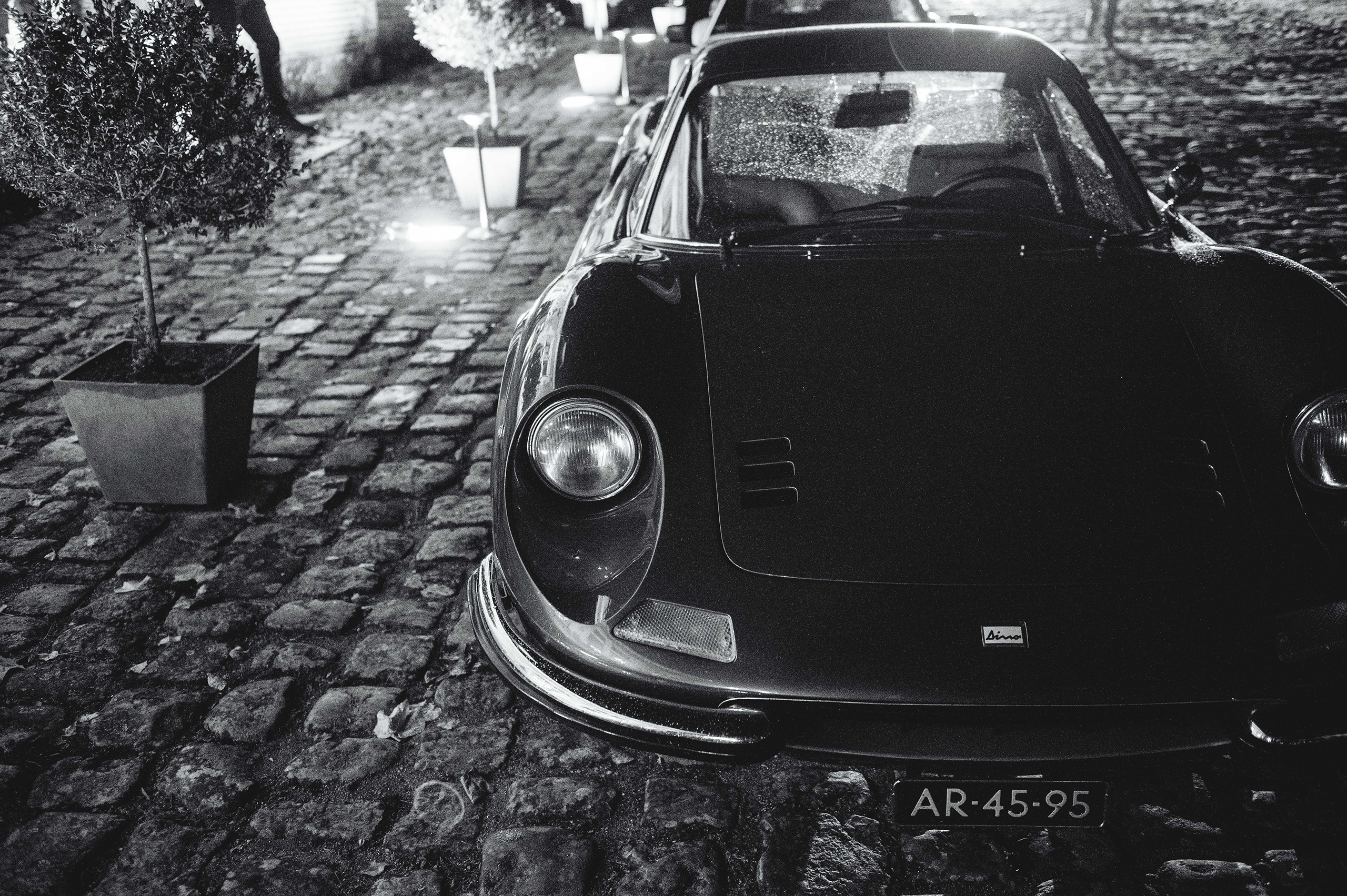

Journées d’Automne 2023

I am not particularly fond of summer – those incredibly long days that disrupt the sense of time and scorching temperatures that turn every activity into a challenge. It’s safe to say I was more than happy to welcome autumn with its charming weather. While personal preferences may vary, I believe that many would agree with me when I say that it’s the most beautiful season of the year. Landscapes are adorned with a golden-brown color palette, and the sun gracefully ascends above mist-covered fields as leaves drift one by one. But for the ones in the know there’s something even more exciting at the horizon; Journées d’Automne!

Annually, as October rolls around, the streets of Beuvardes, nestled within the scenic Aisne department in France, come alive with classic cars representing various eras and origins of the automobile industry. This invite-only event spans three days, commencing with an atmospheric opening barbecue on Friday. It continues on Saturday with a thrilling trackday at the Ecuyers circuit, complete with lunch, dinner, and afterparty at Château de Nesles. Lastly, the weekend concludes with an engaging rally on Sunday, culminating with a lunch at Château de Vic-sur-Aisne.

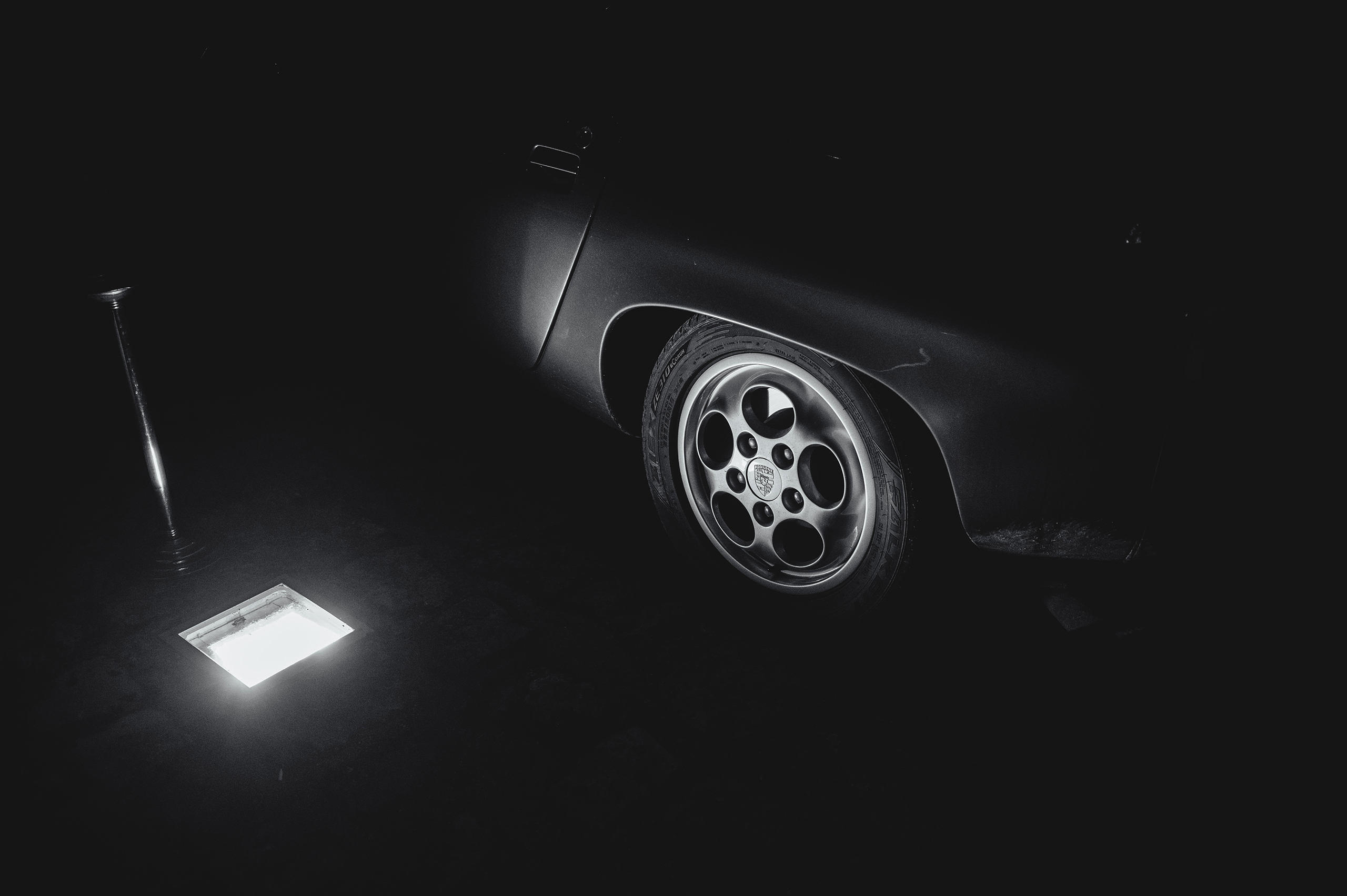

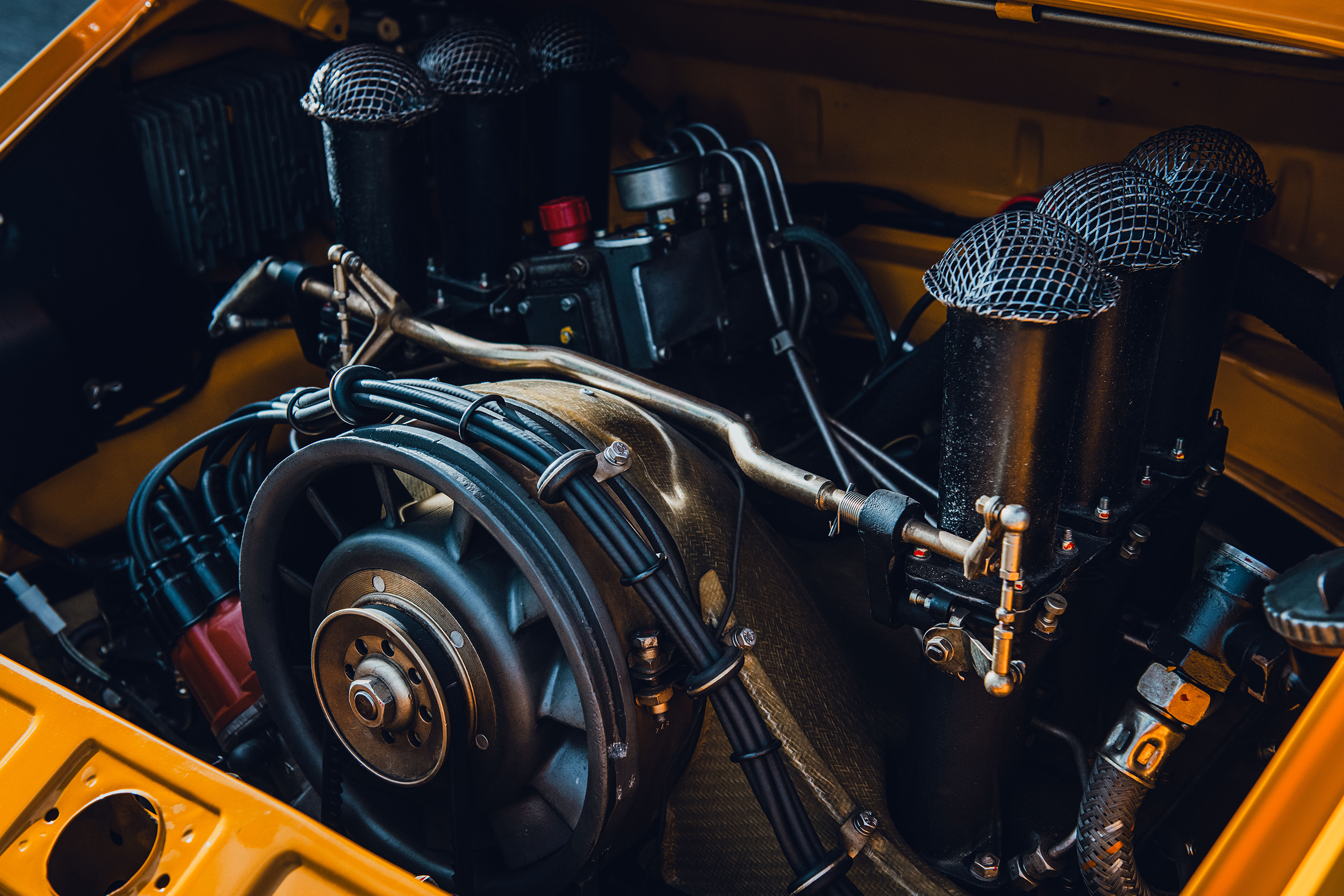

Arthur, who runs his own workshop in the Kortrijk region in Belgium, dedicated to reviving the almost-lost craft of metalshaping and coachbuilding, offered his workshop as the perfect starting point for our trip to set the mood. Arthur himself added a touch of style to the group with his 1972 bright yellow ‘Hell Gelb’ Porsche 911T 2.4. Emile drove his 1974 aubergine-purple ‘faggio’ Alfa Romeo GT1600 Junior, while I assumed the role of co-pilot in a dark blue ‘dunkelblau’ 1987 Porsche 911 3.2 G50 with Ben at the wheel. As the clock’s small hand slowly but surely edged towards vertical, our aim was to reach Beuvardes as quick as possible. Dennis and Pieter had already arrived at the B&B with Dennis’ green ‘Verde Pino’ 1975 Alfa Romeo Giulia Super Nuova. Some of the participants had gathered at the opening barbecue, but we decided to savor a nightcap at our lodging before retiring to our beds.

We were among the first visitors to the paddock at the Circuit. Amid the gentle morning sun, a Jaguar Lister “Knobbly,” Bugatti Type 37, Lotus Elite, and a few Alfa’s were bathing in the warm light, promptly elevating our expectations for the day ahead. Early arrival had both advantages and disadvantages: unfortunately, coffee was not yet served, but it did provide us with the opportunity to see all the participants arrive, giving us a chance to get to know everyone.

Once the clock struck 9, the true enthusiasts were already waiting at the circuit’s entrance. That Bugatti Type 37 from earlier, stood already second in line, right after an Alpine A110. My priority was to get a good cup of coffee. After I joined Ben as co-pilot on track with his Porsche. The asphalt was still wet from the morning dew, causing the rear of the 911 to break loose from time to time.

After this brief session and another cup of coffee, the paddock began to fill. Spanning a range from pre-war classics to the 1980s, and everything in between, including a handful of race cars. Notable among the latter were the 1932 Alfa Romeo 8C 2300, the 1936 Delahaye 135CS, and the 1947 Maserati A6GCS ‘Monofaro’. Yet, my eyes were continually drawn to that green Lotus Elite with a silver roof standing in the 60’s paddock.

As the afternoon progressed, growling stomachs signaled the perfect time for all to gather at the Château de Nesles for lunch. We savored a quintessentially French experience, commencing with an appetizer of charcuterie, followed by a main course of stew with creamy mashed potatoes, all washed down with a generous serving of fine red (or white) wine. A warm and familial ambiance envelops the tables, while the present photographers, including myself, gathered at the entrance of the tower located at the corner of the château’s yard. Ascending the steep stone stairs, requiring careful concentration, brought us to the tower’s summit. In this spot the already iconic image was captured that encapsulates the essence of ‘Journées d’Automne’: A diverse collection of vintage cars against the stunning backdrop that characterizes the Champagne region in France.

In the afternoon I had the privilege of taking the driver’s seat in Ben’s 1987 Porsche 911 for a few laps around track. Thank you for your trust and sharing your passion, Ben. Although I have some fundamental experience with sports cars, I had never set foot on a race track before. Fortunately, the Porsche 911’s remarkable responsiveness left no room for doubt; it clearly communicated its expectations and where it desired to go. This experience has transformed a long-held aspiration—circuit driving—into a wonderful reality. After a few laps as a passenger alongside Dennis, who skillfully handled his Giulia, and with Thibaut in his Delahaye, an unique experience in its own right, coupled with engaging interactions with fellow participants, it became evident that the type of car you own matters less than the passion you bring to it. And with this beautiful mindset, the paddock emptied as the sun had long hidden behind gray and dark clouds.

Much like lunch, dinner unfolded at Château de Nesles, but an entirely different ambiance blanketed the estate’s courtyard. The guests were elegantly attired, each holding a glass of champagne, a cocktail, or a non-alcoholic beverage, as they congregated in a corner of the yard. Amidst the dazzling headlights, we engaged in friendly banter, attempting to identify the arriving cars by their distinctive silhouettes.

After a round of cocktails and jokes, time for dinner had arrived. The cuisine was nothing short of exquisite, even though the specifics have become somewhat hazy in my memory. The wine, too, was exceptional! Following a dessert, the festivities shifted to the opposite end of the yard, where the “talon pointe” – afterparty continued well into the late hours of the night.

At 7 o’clock in the morning, I rose from my slumber, free of any lingering regrets from the previous night. I was all geared up for the oldtimer rally, as it usually takes place on Sunday. Given that the track day had allowed everyone to indulge in some high-speed excitement the day before, there was air of relaxation among the participants. Perhaps it was also due to the fact that the Champagne region in the morning unveiled a breathtaking scenery, an absolute joy that required just a moment of quiet appreciation to savor its full beauty.

Following a coffee break in a quaint, ancient village, where the cobblestone road gave the distinct sensation of travelling back in time (or perhaps time had stood still here?), we embarked on a final 40-kilometer drive toward Château de Vic-sur-Aisne for one final lunch. Handshakes were warmly exchanged and hugs were given. The time had come to make our way back home, With just one final stretch of our journey left to complete. Dealing with the wind and eating flies In the Delahaye kept me awake on the drive home.

Merci Etienne et Guillaume !

À l’année prochaine, Journées d’Automne !